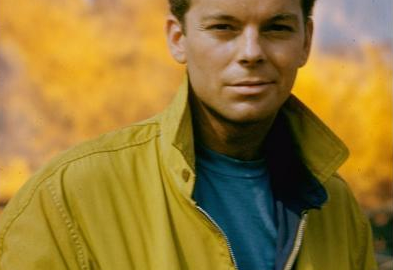

Kirk Douglas (born Issur Danielovitch December 9, 1916) is an American

retired actor, filmmaker, and author. A centenarian, he is one of the last

surviving stars of the film industry’s Golden Age.

After an impoverished childhood with immigrant parents and six sisters, he made his film debut in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946) with Barbara Stanwyck and

Lizabeth Scott. Douglas soon developed into a leading box-office star

throughout the 1950s, known for serious dramas, including westerns and

war movies. During his career, he appeared in more than 90 movies.

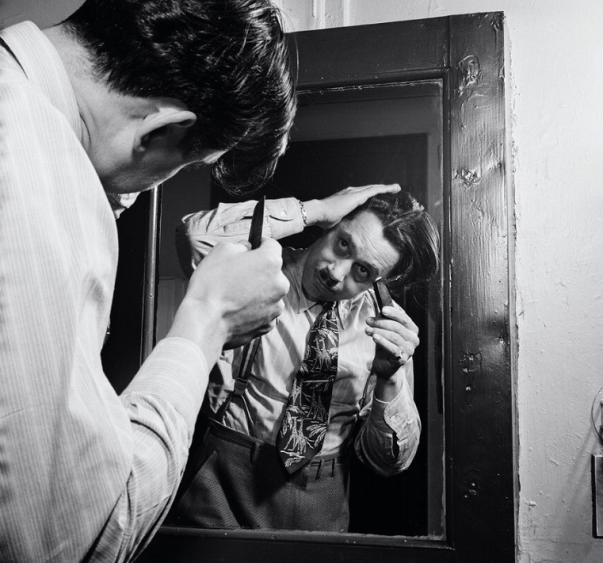

Douglas is known for his explosive acting style, which he displayed as a

criminal defense attorney in Town Without Pity (1961).

Douglas became an international star through positive reception for his

leading role as an unscrupulous boxing hero in Champion (1949), which

brought him his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Other early films include Young Man with a Horn (1950), playing opposite

Lauren Bacall and Doris Day, Ace in the Hole opposite Jan Sterling (1951), and Detective Story (1951), for which he received a Golden Globe

nomination as Best Actor in a Drama. He received a second Oscar

nomination for his dramatic role in The Bad and the Beautiful (1952),

opposite Lana Turner, and his third nomination for portraying Vincent van

Gogh in Lust for Life (1956), which landed him a second Golden Globe

nomination.

In 1955, he established Bryna Productions, which began producing films as

varied as Paths of Glory (1957) and Spartacus (1960). In those two films,

he collaborated with the then-relatively-unknown director Stanley Kubrick,

taking lead roles in both films. Douglas has been praised for helping to

break the Hollywood blacklist by having Dalton Trumbo write Spartacus

with an official on-screen credit. He produced and starred in Lonely Are

the Brave (1962), considered a classic, and Seven Days in May (1964),

opposite Burt Lancaster, with whom he made seven films. In 1963, he

starred in the Broadway play One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a story

he purchased and later gave to his son Michael Douglas, who turned it

into an Oscar-winning film.

As an actor and philanthropist, Douglas has received three Academy

Award nominations, an Oscar for Lifetime Achievement, and the

Presidential Medal of Freedom. As an author, he has written ten novels and

memoirs. He is No. 17 on the American Film Institute’s list of the greatest

male screen legends of classic Hollywood cinema, the highest-ranked living

person on the list. After barely surviving a helicopter crash in 1991, and then

suffering a stroke in 1996, he has focused on renewing his spiritual and

religious life. He lives with his second wife (of 65 years), Anne Buydens, a

producer.

Early life and education

Douglas was born Issur Danielovitch. His father’s brother, who immigrated earlier, used the surname Demsky, which Douglas’s family adopted in the United States. Douglas grew up as

Izzy Demsky and legally changed his name to Kirk Douglas before entering the United States Navy during World War II.

In his 1988 autobiography, The Ragman’s Son, Douglas notes the hardships that he, along with six sisters and his parents, endured during their early years in Amsterdam, New York:

My father, who had been a horse trader in Russia, got himself a horse and a small wagon, and became a ragman, buying old rags, pieces of metal, and junk for pennies, nickels, and dimes…. Even on Eagle Street, in the poorest section of town, where all the families were struggling, the ragman was on the lowest rung on the ladder. And I was the ragman’s son.

Growing up, Douglas sold snacks to mill workers to earn enough to buy milk and bread to help his family. Later, he delivered newspapers and during his youth he had more than forty jobs before becoming an actor. He found living in a family with six sisters to be stifling: “I was dying to get out. In a sense, it lit a fire under me.”

In high school, after acting in plays, he knew he wanted to become a professional actor. Unable to afford thetuition, Douglas talked his way into the dean’ office at St. Lawrence

University and showed him a list of his high school honors. He received a loan which he paid back by working part-time as a gardener and a janitor. He was a standout on the wrestling team and wrestled one summer in a carnival to make money.

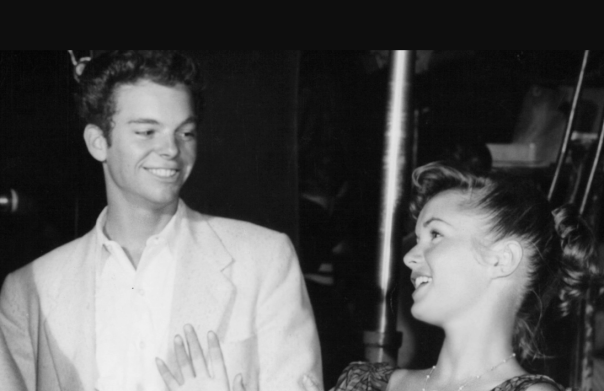

Douglas’s acting talents were noticed at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City, which gave him a special scholarship. One of his classmates was Betty Joan Perske (later known as Lauren Bacall), who would play an important role in launching his film career. Bacall wrote that she “had a wild crush on Kirk,” and they dated casually.

Another classmate, and a friend of Bacall’s, was aspiring actress Diana Dill, who would later become Douglas’s first wife. During their time together, Bacall learned Douglas had no money, and that he once spent the night in jail since he had no place to sleep. She once

gave him her uncle’s old coat to keep warm: “I thought he must be frozen in the winter. … He was thrilled and grateful.” Sometimes, just to see him, she would drag a friend or her mother to the restaurant where he worked as a busboy and waiter.

He told her his dream was to someday bring his family to New York to see him on stage. During that period, she fantasized about someday sharing her personal and stage lives with Douglas, but would later be disappointed: “Kirk did not really pursue me. He was friendly and sweet—enjoyed my company—but I was clearly too young for him,” the

eight-years-younger Bacall later wrote.

Early career

Douglas first wanted to be an actor after he recited the poem The Red Robin of Spring while in kindergarten and received applause. He enlisted in the United States Navy in 1941, shortly after the United States entered World War II, where he served as a communications officer in anti- submarine warfare aboard USS PC-1137. He was medically discharged in

Douglas first wanted to be an actor after he recited the poem The Red Robin of Spring while in kindergarten and received applause. He enlisted in the United States Navy in 1941, shortly after the United States entered World War II, where he served as a communications officer in anti- submarine warfare aboard USS PC-1137. He was medically discharged in

1944 for war injuries sustained from the accidental dropping of a depth charge.

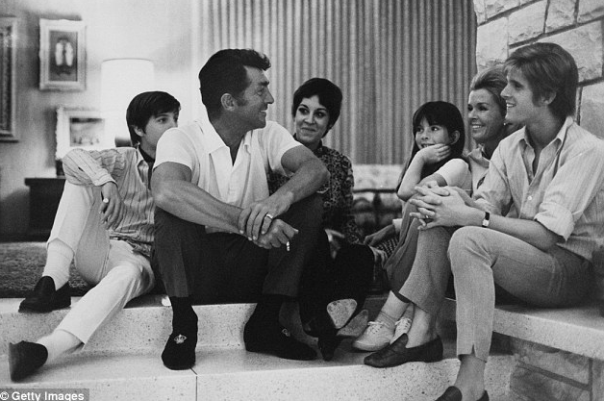

He married Diana Dill on November 2, 1943. They had two sons, Michael in 1944 and Joel in 1947, before they divorced in 1951. After the war, Douglas returned to New York City and found work in radio, theater and commercials. In his radio work, he acted in network soap

operas, and sees those experiences as being especially valuable, as a skill in using one’s voice is important for aspiring actors, and regrets that the same avenues are no longer available.

His stage break occurred when he took over the role played by Richard Widmark in Kiss and Tell (1943), which then led to other offers. Douglas had planned to remain a stage actor, until his friend, Lauren Bacall helped him get his first film role by recommending him to producer Hal B. Wallis, who was looking for a new male talent. Wallis’ film, The

Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), with Barbara Stanwyck, became Douglas’s debut screen appearance. He played a young, insecure man, stung with jealousy, whose life was dominated by his ruthless wife, and he hid his feelings with alcohol. It would be the last time that Douglas portrayed a weakling in a film role.

Reviewers of the film noted that Douglas already projected qualities of a “natural film actor” with the similarity of this role with later ones explained by biographer Tony Thomas:

His style and his personality came across on the screen, something that does not always

happen, even with the finest actors. Douglas had, and has, a distinctly individual manner. He radiates a certain inexplicable quality, and it is this, as much as talent, that accounts for his success in films.

Career

1940s

Douglas’s image as a tough guy was established in his eighth film, Champion (1949), after producer Stanley Kramer chose him to play a selfish boxer. In accepting the role, he took a gamble, however, since he had to turn down an offer to star in a big-budget MGM film, The Great Sinner, which would have earned him three times the income. Film historian Ray Didinger says, “he saw Champion as a greater risk, but also a greater opportunity… Douglas took the part and absolutely nailed it.” Frederick Romano, another sports film historian, described Douglas’s acting as “alarmingly authentic: Douglas shows great concentration in the ring. His intense focus on his opponent draws the viewer into the ring.

Perhaps his best characteristic is his patented snarl and grimace … he leaves no doubt that he is a man on a mission.”

Douglas received his first Academy Award nomination and the film earned six nominations in all. Variety magazine called it “a stark, realistic study of the boxing rackets.” From that film on, he decided that to succeed as a star, he needed to ramp up his intensity, overcome his natural shyness, and choose stronger roles. He later stated, “I don’t think I’d be much of an actor without vanity. And I’m not interested in being a ‘modest actor.'”

Early in his Hollywood career, he demonstrated his independent streak and broke his studio contracts to gain total control over his projects, forming his own movie company, Bryna Productions, named after his mother. In 1947 Douglas made Out of the

Past (UK: Build My Gallows High). He starred in this film with Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer. Douglas made his Broadway debut in 1949 in Three Sisters, produced by Katharine Cornell.

1950s

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Douglas was a major box-office star, playing opposite some of the leading actresses of that era. He played a frontier peace officer in his first western, Along the Great Divide (1951). He quickly became very comfortable with riding horses and playing gunslingers, and appeared in many westerns. He considers Lonely Are the Brave (1962), in which he plays a cowboy trying to live by his own code, as his personal favorite. The film, written by Dalton Trumbo, was respected by critics, but did not do well at the box office due to poor marketing and distribution.

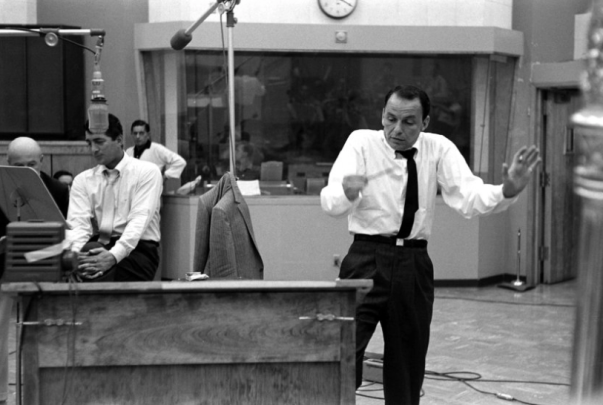

In 1950, Douglas played Rick Martin in Young Man with a Horn, based on a novel of the same name by Dorothy Baker inspired by the life of Bix Beiderbecke, the jazz cornetist. Composer-pianist Hoagy Carmichael, playing the sidekick role, added realism to the film and gave Douglas insight into the role, being a friend of the real Beiderbecke. Doris Day

starred as Jo, a young woman who was infatuated with the struggling jazz musician. This was strikingly opposite of the real-life account in Doris Day’s autobiography, which described Douglas as “civil but self-centered,” and the film as “utterly joyless.” During filming, bit actress Jean Spangler disappeared and her case remains unsolved. On October 9, 1949, Spangler’s purse was found near the Fern Dell entrance to Griffith Park in

Los Angeles. There was an unfinished note in the purse addressed to a “Kirk,” which read:

Can’t wait any longer, Going to see Dr. Scott. It will work best this way while mother is away.” Douglas, married at the time, called the police and told them he was not the Kirk mentioned in the note. When interviewed via telephone by the head of the investigating team, Douglas stated that he had “talked and kidded with her a bit” on set, but that he had never been out with her. Spangler’s girlfriends told police that she was three months pregnant when she disappeared and that she had talked about having an abortion, which was illegal at that time.

In 1951, Douglas starred as a newspaper reporter anxiously looking for a big story in Ace in the Hole, director Billy Wilder’s first effort as both writer and producer. The subject and story was controversial at the time, and U.S. audiences stayed away. Some reviews saw it as “ruthless and cynical … a distorted study of corruption, mob psychology and the free press.” Possibly it “hit too close to home,” says Douglas. It won a best foreign film award at

the Venice Film Festival. The film’s stature has increased in recent years, with some surveys placing it in their top 500 films list. Woody Allen considers it one of his favorite films. As the film’s star and protagonist, Douglas is credited for the intensity of his acting. Roger Ebert described Douglas’s “focus and energy … almost scary. There is nothing dated about [his] performance. It’s as right now as a sharpened knife.” Biographer Gene Philips notes that Wilder’s story was “galvanized” by Douglas’s “astounding performance,” and no doubt was a factor when George Stevens, who presented Douglas with the AFI Life Achievement Award in 1991, said of him: “No other leading actor was ever more ready to tap the dark, desperate side of the soul and thus to reveal the complexity of human nature.”

Also in 1951, Douglas starred in Detective Story, nominated for four Academy Awards, including one for Lee Grant in her debut film. Grant said Douglas was “dazzling, both personally and in the part. … He was a big, big star. Gorgeous. Intense. Amazing.” To prepare for the role, he spent days with the New York police department and sat in on interrogations. Reviewers recognized Douglas’s acting qualities, with Bosley Crowther

describing Douglas as “forceful and aggressive as the detective.”

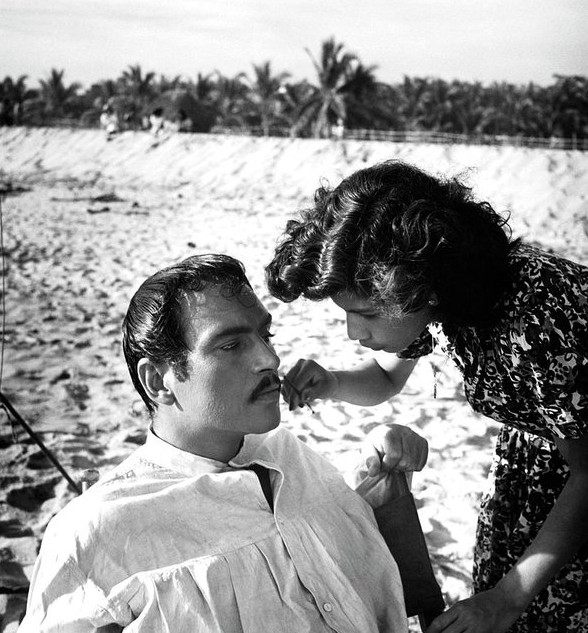

In The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), another of his three Oscar-nominated roles, Douglas plays a hard-nosed film producer who manipulates and uses his actors, writers, and directors. Bacall and Doris Day played two very different types of women in his life. In 1954 Douglas starred in Ulysses from Homer’s epic poem Odyssey, with Silvana Mangano as Penelope and Circe, and Anthony Quinn playing Antinous. The film director Mario Camerini co-wrote the screenplay with writer Franco Brusati.

In 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Douglas showed that in addition to serious, driven characters, he was adept at roles requiring a lighter, comic touch. In this adaptation of the Jules Verne novel, he played a happy-go-lucky sailor who was the opposite in every way to the brooding Captain Nemo (James Mason). The film was one of Walt Disney’s most successful live-action movies and a major box-office hit. He managed a similar comic turn in the western Man Without a Star (1955) and in For Love or Money (1963). He showed further diversity in one of his earlies television appearances. He was a musical guest (as himself) on The Jack Benny Program (1954).

In 1955, Douglas formed his own movie company, Bryna Productions, named after his mother. To do so, he had to break contracts with Hal B. Wallis and Warner Bros., but began to produce and star in his own films, including Paths of Glory (1957), The Vikings (1958), Spartacus (1960), Lonely are the Brave (1962) and Seven Days in May (1964).

While Paths of Glory did not do well at the box office, it has since become one of the great anti-war films, and one of early films by director Stanley Kubrick. Douglas, a fluent French speaker, plays a sympathetic French officer during World War I who tries to save three soldiers from the firing squad. Biographer Vincent LoBrutto describes Douglas’s “seething but controlled portrayal exploding with the passion of his convictions at the

injustice levelled at his men.” The film was banned in France until 1976.

Before production of the film began, however, Douglas and Kubrick had to work out some major issues, one of which was Kubrick’s rewriting the screenplay without informing Douglas first. It led to their first major argument: “I called Stanley to my room … I hit the ceiling. I called him every four-letter word I could think of … ; I got the money, based on that [original] script. Not this shit! I threw the script across the room. We’re going back to

the original script, or w’re not making the picture. Stanley never blinked an eye. We shot the original script. I think the movie is a classic, one of the most important pictures—possibly the most important picture—Stanley Kubrick has ever made.”

Douglas played military men in numerous films, with varying nuance, including Top Secret Affair (1957), Town Without Pity (1961), The Hook (1963), Seven Days in May (1964), Heroes of Telemark (1965), In Harm’s Way (1965), Cast a Giant Shadow (1966), Is Paris Burning (1966), The Final Countdown (1980), and Saturn 3 (1980). His acting style and delivery made him a favorite with television impersonators such as Frank Gorshin, Rich Little and David Frye.

His role as Vincent van Gogh in Lust for Life (1956), directed by Vincente Minnelli and based on Irving Stone’s best-seller, was filmed mostly on location in France. Douglas was noted not only for the veracity of van Gogh’s appearance but for how he conveyed the painter’s internal turmoil. Some reviewers consider it the most famous example of the “tortured artist” who seeks solace from life’s pain through his work. Others see it as a portrayal not only of the “painter-as-hero,” but a unique presentation of the “action painter,” with Douglas expressing the physicality and emotion of painting, as he uses the canvas to capture a moment in time.

Douglas was nominated for an Academy Award for the role, with his co-star Anthony Quinn winning the Best Supporting Actor Oscar as Paul Gauguin, van Gogh’s friend. Douglas won a Golden Globe award, although Minnelli said Douglas should have won an Oscar: “He achieved a moving and memorable portrait of the artist—a man of massive creative power,

triggered by severe emotional stress, the fear and horror of madness.” Douglas himself called his acting role as Van Gogh a painful experience: “Not only did I look like Van Gogh, I was the same age he was when he committed suicide.

His wife said he often remained in character in his personal life: “When he was doing Lust for Life, he came home in that red beard of Van Gogh’s, wearing those big boots, stomping around the house—it was frightening.”

In general, however, Douglas’s acting style fit well with Minnelli’s preference for “melodrama and neurotic-artist roles,” writes film historian, James Naremore. He adds that Minnelli had his “richest, most impressive collaborations” with Douglas, and for Minnelli, no other actor portrayed his level of ‘cool.’ A robust, athletic, sometimes explosive player, Douglas loved stagy rhetoric, and he did everything passionately.” That level of

passion in Douglas&’s persona was also used effectively by Minnelli in The Bad and the Beautiful, four years earlier, for which Douglas was nominated for Best Actor, with the film winning five Oscars.

1960s

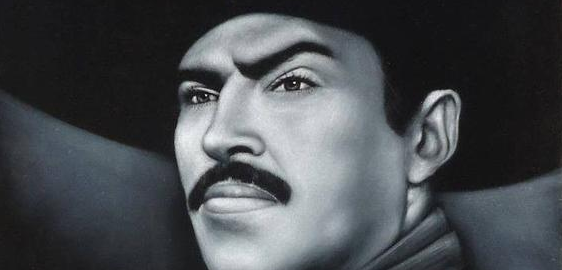

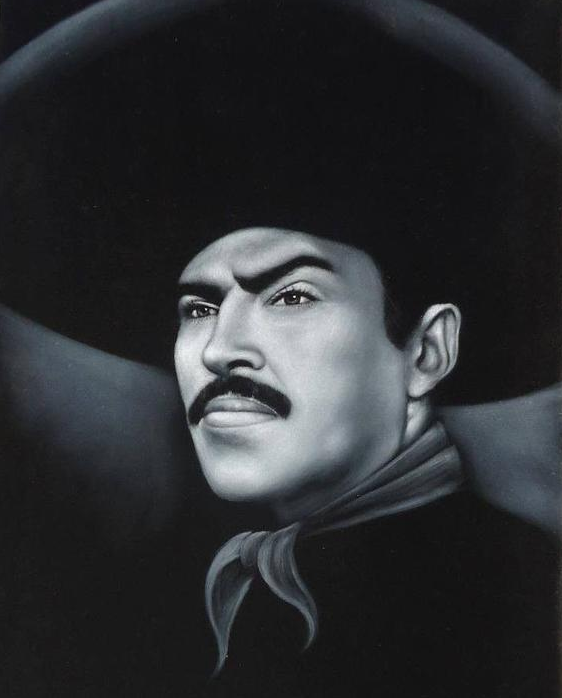

In 1960, Douglas played the title role in what many consider his career defining appearance as the Thracian slave rebel Spartacus with an all-star cast in Spartacus (1960). He was the executive producer as well, and raised the $12 million production cost that made it one of the most expensive films up to that time. Douglas initially selected Anthony Mann to direct, but replaced him early on with Stanley Kubrick, with whom he previously collaborated in Paths of Glory.

When the film was released, Douglas gave full credit to its screenwriter, Dalton Trumbo, who was on the Hollywood blacklist, and thereby effectively ended it. About that event, he said, “Ive made over 85 pictures, but the thing I’m most proud of is breaking the blacklist.” However the film’s producer Edward Lewis and the family of Dalton Trumbo publicly disputed Douglas’s claim. In the film Trumbo (2015), Douglas is portrayed by Dean

Gorman.

Douglas bought the rights to the novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest from its author, Ken Kesey. He turned it into a play in 1963 in which he starred, and it ran on Broadway for five months. Reviews were mixed. Douglas retained the movie rights, but after a decade of being unable to find a producer, gave the rights to his son, Michael. In 1975, the film version was produced by Michael Douglas and Saul Zaentz, and starred Jack Nicholson, as Douglas was then considered too old to play the character as written. It won all five major Academy Awards, only the second to achieve that, including one for Nicholson.

Douglas made seven films over the decades with Burt Lancaster: I Walk Alone (1948), Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), The Devil’s Disciple (1959), The List of Adrian Messenger (1963), Seven Days in May (1964), Victory at Entebbe (1976) and Tough Guys (1986), which fixed the notion of the pair as something of a team in the public imagination. Douglas was

always second-billed under Lancaster in these movies but, with the exception of I Walk Alone, in which Douglas played a villain, their roles were more or less the same size. Both actors arrived in Hollywood at the same time, and first appeared together in the fourth film for each, albeit with Douglas in a supporting role. They both became actor-producers who

sought out independent Hollywood careers.

John Frankenheimer, who directed the political thriller Seven Days in May in 1964, had not worked well with Lancaster in the past, and originally did not want him in this film. However, Douglas thought Lancaster would fit the part and “begged me to reconsider,” said Frankenheimer, and he then gave Lancaster the most colorful role. “It turns out that Burt Lancaster and I got along magnificently well on the picture,” he later said.

In 1967 Douglas starred with John Wayne in the western film directed by Burt Kennedy titled The War Wagon. In The Arrangement (1969), a drama directed by Elia Kazan, based upon his novel of the same title, Douglas starred as a tormented advertising executive, with Faye Dunaway as costar. The film did poorly at the box office, receiving mostly negative reviews, while Dunaway felt many of the reviews were unfair, writing in her biography, “I can’t understand it when people knock Kirk’s performance, because I think he’s terrific in the picture,” adding that “he’s as bright a person as I’ve met in the acting

profession.” She says that his “pragmatic approach to acting” would later be “a philosophy that ended up rubbing off on me.”

1970s–2010s

Between 1970 and 2008, Douglas made nearly 40 movies and appeared

on various television shows. He starred in a western, There Was a Crooked

Man… (1970), alongside Henry Fonda. The film was produced and directed

by Joseph L. Mankiewicz.

In 1972, he was a guest in David Winters’ television special The London Bridge Special, starring Tom Jones. In 1973, he directed his first film, Scalawag. That same year, Douglas

reunited with director David Winters and appeared in the made-for-TV musical version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (nominated for three Emmys)alongside Stanley Holloway, and Donald Pleasence.

He returned to the director’s chair for Posse (1975), in which he starred alongside Bruce Dern. In 1978, he costarred with John Cassavetes and Amy Irving in a horror film, The Fury, directed by Brian De Palma. In 1980, he starred in The Final Countdown, playing the commanding officer of the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz, which travels through time to the day before the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. It was produced by his son Peter Douglas. In

1982, he starred in The Man from Snowy River, an Australian film which received critical acclaim and numerous awards. In 1986, he reunited with his longtime costar, Burt Lancaster, in a crime comedy, Tough Guys, which included Charles Durning and Eli Wallach. It marked the final collaboration between Douglas and Lancaster, completing a partnership of more than 40 years.

In 1986, he co-hosted (with Angela Lansbury) the New York Philharmonic’s tribute to the 100th anniversary of the Statue of Liberty. The symphony was conducted by Zubin Mehta. In 1988, Douglas starred in a television adaptation of Inherit the Wind, opposite Jason Robards and Jean Simmons. The film won two EmmyAwards.

In the 1990s, Douglas continued starring in various features. Among them was The Secret in 1992, a television movie about a grandfather and his grandson who both struggle with dyslexia. That same year, he played the uncle of Michael J. Fox in a comedy, Greedy. He appeared as the Devil in the video for the Don Henley song “The Garden of Allah.” In 1996, after suffering a severe stroke which impaired his ability to speak, Douglas still wanted to make movies. He underwent years of voice therapy and made Diamonds in 1999, in which he played an old prizefighter who was recovering from a stroke. It costarred his longtime friend from his early years, Lauren Bacall.

In 2003, Michael and Joel Douglas produced It Runs in the Family, which along with Kirk starred various family members, including Michael, Michael’s son, and his wife from 50 years earlier, Diana Dill, playing his wife. In March 2009, Douglas did an autobiographical one-man show, Before I Forget, at the Center Theatre Group’s Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City, California. The four performances were filmed and turned into a documentary that was first screened in January 2010.Douglas appeared at the 2018 Golden Globes at the age of 101 with his daughter-in-law Catherine Zeta-Jones; he received a standing ovation and helped to present the award for Best Screenplay – Motion Picture. This was a rare appearance for Douglas, who suffered a stroke 20 years prior, and his first at a major awards show since the Oscars in 2011.

Style and philosophy of acting

Kirk is one of a kind. He has an overpowering physical presence, which is why on a

large movie screen he looms over the audience like a tidal wave in full flood. Globally

revered, he is now the last living screen legend of those who vaulted to stardom at the

war’s end, that special breed of movie idol instantly recognizable anywhere, whose

luminous on-screen characters are forever memorable.

—Jack Valenti, president of the Motion Picture Association of America.

Douglas stated that the keys to acting success are determination and application: “You must know how to function and how to maintain yourself, and you must have a love of what you do. But an actor also needs great good luck. I have had that luck.” Douglas had great vitality and explained that, “it takes a lot out of you to work in this business. Many people fall by the wayside because they don’t have the energy to sustain their talent.”

That attitude toward acting became evident with Champion (1949). From that one role, writes biographer John Parker, he went from stardom and entered the superleague, where his style was in marked contrast to Hollywood’s other leading men at the time. His sudden rise to prominence is explained and compared to that of Jack Nicholson’s: He virtually ignored interventionist directors. He prepared himself privately for each role he

played, so that when the cameras were ready to roll he was suitably, and some would say egotistically and even selfishly, inspired to steal every scene in a manner comparable in modern times to Jack Nicholson’s modus operandi.

As a producer, Douglas had a reputation of being a compulsively hard worker who expected others to exude the same level of energy. As such, he was typically demanding and direct in his dealing with people who worked on his projects, with his intensity spilling over into all elements of his film-making. This was partly due to his high opinion of actors, movies, and moviemaking: “To me it is the most important art form—it is an art, and

it includes all the elements of the modern age.” He also stressed prioritizing the entertainment goal of films over any messages, “You can make a statement, you can say something, but it must be entertaining.”

As an actor, he dived into every role, dissecting not only his own lines but all the parts in the script to measure the rightness of the role, and he was willing to fight with a director if he felt justified. Melville Shavelson, who produced and directed Cast a Giant Shadow (1966), said that it didn’t take him long to discover what his main problem was going to be in directing Douglas: Kirk Douglas was intelligent. When discussing a script with actors,

I have always found it necessary to remember that they never read the other actors’ lines, so their concept of the story is somewhat hazy. Kirk had not only read the lines of everyone in the picture, he had also read the stage directions … Kirk, I was to discover, always read every word, discussed every word, always argued every scene, until he was convinced

of its correctness. … He listened, so it was necessary to fight every minute.

For most of his career, Douglas enjoyed good health and what seemed like an inexhaustible supply of energy. He attributed much of that vitality to his childhood and pre-acting years: “The drive that got me out of my hometown and through college is part of the makeup that I utilize in my work. It’s a constant fight, and it’s tough.” His demands on others, however, were an expression of the demands he placed on himself, rooted in his youth.

“It took me years to concentrate on being a human being—I was too busy scrounging for money and food, and struggling to better myself.”

Actress Lee Grant, who acted with him and later filmed a documentary about him and his family, notes that even after he achieved worldwide stardom, his father would not acknowledge his success. He said”nothing. Ever.” Douglas’s wife, Anne, similarly attributes the energy he devotes to acting to his tough childhood: “He was reared by his mother and his sisters and as a schoolboy he had to work to help support the family. I think part of

Kirk’s life has been a monstrous effort to prove himself and gain recognition in the eyes of his father … Not even four years of psychoanalysis could alter the drives that began as a desire to prove himself.”

Douglas has credited his mother, Bryna, for instilling in him the importance of “gambling on yourself;” and he kept her advice in mind when making films. Bryna Productions was named in her honor. Douglas realized that his intense style of acting was something of a shield: “Acting is the most direct way of escaping reality, and in my case it was a means of escaping a drab and dismal background.”

Personal life

In The Ragman’s Son, Douglas described himself as a “sonofabitch,” adding, “I’m probably the most disliked actor in Hollywood. And I feel pretty good about it. Because that’s me…. I was born aggressive, and I guess I’ll die aggressive.” Co-workers and associates alike noted similar traits, with Burt Lancaster once remarking, “Kirk would be the first to tell you that he is a very difficult man. And I would be the second.”

Douglas’ personality is attributed to his difficult upbringing living in poverty and his aggressive alcoholic father who was neglectful of Kirk as a young child. According to

Douglas, “there was an awful lot of rage churning around inside me, rage that I was afraid to reveal because there was so much more of it, and so much stronger, in my father.” Douglas’ discipline, wit and sense of humor is also often recognized.

Anne Buydens and Douglas at the 2003 Jefferson Awards for Public Service ceremony

Anne Buydens and Douglas at the 2003 Jefferson Awards for Public Service ceremony

Douglas and his first wife, Diana Dill, married on November 2, 1943. They had two sons, actor Michael Douglas and producer Joel Douglas, before divorcing in 1951. Afterwards, in Paris, he met producer Anne Buydens (born Hannelore Marx; April 23, 1919, Hanover, Germany) while acting on location in Lust for Life. She originally fled from Germany to escape Nazism and survived by putting her multilingual skills to work at a film studio, doing translations for subtitles. They married on May 29, 1954.

In 2014, they celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary at the Greystone Mansion in

Beverly Hills. They had two sons, Peter, a producer, and Eric, an actor who died on July 6, 2004, from an overdose of alcohol and drugs. In 2017, the couple released a book, Kirk and Anne: Letters of Love, Laughter and a Lifetime in Hollywood, that revealed intimate letters they shared through the years. Throughout their marriage, Douglas had affairs with other women including several Hollywood starlets, though he never hid his infidelities

from his wife who was accepting of them and explained, “as a European, I

understood it was unrealistic to expect total fidelity in a marriage.”

In February 1991, Douglas was in a helicopter and was injured when the aircraft collided with a small plane above Santa Paula Airport. Two other people were also injured; two people in the plane were killed. This near- death experience sparked a search for meaning by Douglas, which led him, after much study, to embrace the Judaism in which he had been raised. He documented this spiritual journey in his book, Climbing the Mountain: My

Search for Meaning (2001).

In his earlier autobiography, The Ragman’s Son, he recalled, “years back, I tried to forget that I was a Jew,” but later in his career he began “coming to grips with what it means to be a Jew,” which became a theme in his life. In an interview in 2000, he explained this transition: Judaism and I parted ways a long time ago, when I was a poor kid growing up in Amsterdam, N.Y. Back then, I was pretty good in cheder, so the Jews of our community

thought they would do a wonderful thing and collect enough money to send me to a yeshiva to become a rabbi. Holy Moses! That scared the hell out of me. I didn’t want to be a rabbi. I wanted to be an actor. Believe me, the members of the Sons of Israel were persistent. I had nightmares – wearing long payos and a black hat. I had to work very hard to get out of it. But it took me a long time to learn that you don’t have to be a rabbi to be a Jew.

Douglas notes that the underlying theme of some of his films, including The Juggler (1953), Cast a Giant Shadow (1966), and Remembrance of Love (1982), was about “a Jew who doesn’t think of himself as one, and eventually finds his Jewishness.” The Juggler was the first Hollywood feature to be filmed in the newly established state of Israel. Douglas recalls that while there, he saw “extreme poverty and food being rationed.” But he

found it “wonderful, finally, to be in the majority.”; Its producer, Stanley Kramer, tried to portray “Israel as the Jews’ heroic response to Hitler’s destruction.” Although his children had non-Jewish mothers, Douglas states that they were “aware culturally” of his “eep convictions,” and he never tried to influence their own religious decisions. Douglas’s wife, Anne, converted to Judaism before they renewed their wedding vows in 2004. Douglas

celebrated a second Bar-Mitzvah ceremony in 1999, aged 83.

Douglas and his wife have donated to various non-profit causes during his career, and are planning on donating most of their $80 million net worth. Among the donations have been those to his former high school and college. In September 2001, he helped fund his high school’s musical, Amsterdam Oratorio, composed by Maria Riccio Bryce, who won the

school Thespian Society’s Kirk Douglas Award in 1968. In 2012 he donated $5 million to St. Lawrence University, his alma mater. The college used the donation for the scholarship fund he began in 1999. He has donated to various schools, medical facilities and other non-profit organizations in southern California. These have included the rebuilding of over 400 Los Angeles Unified School District playgrounds that were aged and in need of restoration. They established the Anne Douglas Center for Homeless Women at the Los Angeles Mission, which has helped hundreds of women turn their lives around. In Culver City, they opened the Kirk Douglas Theatre in 2004. They supported the Anne Douglas Childhood

Center at the Sinai Temple of Westwood. In March 2015, Kirk and his wife donated $2.3 million to the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Since the early 1990s Kirk and Anne Douglas have donated up to $40 million to Harry’s Haven, an Alzheimer’s treatment facility in Woodland Hills, to care for patients at the Motion Picture Home. To celebrate his 99th birthday in December 2015, they donated another $15 million to help expand the facility with a new two-story Kirk Douglas Care Pavilion. Douglas has donated a number of playgrounds in Jerusalem, and donated

the Kirk Douglas Theater at the Aish Center across from the Western Wall.

The couple have been involved in numerous volunteer and philanthropic activities. They traveled to more than 40 countries, at their own expense, to act as goodwill ambassadors for the U.S. Information Agency, speaking to audiences about why democracy works and what freedom means. In 1980, Douglas flew to Cairo to talk with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. For all his goodwill efforts, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from

President Jimmy Carter in 1981. At the ceremony, Carter said that Douglas had “done this in a sacrificial way, almost invariably without fanfare and without claiming any personal credit or acclaim for himself.”

In subsequent years, Douglas testified before Congress about elder abuse. Douglas has been a lifelong member of the Democratic Party. He has written letters to politicians who were friends. He notes in his memoir, Let’s Face It (2007), that he felt compelled to write to former president Jimmy Carter in 2006 in order to stress that “Israel is the only successful

democracy in the Middle East … [and] has had to endure many wars against overwhelming odds. If Israel loses one war, they lose Israel.”

Douglas recalled an incident involving his son Eric, who at the time was a friend of Ronald Reagan’s son Ron. When the younger Douglas saw a Barry Goldwater bumper sticker on the Reagans’ car, he shouted “;Boo Goldwater!” In response, Nancy Reagan telephoned the elder Douglas and said, “Come pick up this boy at once.” Kirk said of this that it was “a

sentiment I confess he picked up from me.”

On January 28, 1996, he suffered a severe stroke, which impaired his ability to speak. Doctors told his wife that unless there was rapid improvement, the loss of the ability to speak was likely permanent. After a regime of daily speech-language therapy that lasted several months, his ability to speak returned, although it was still limited. He was able to accept an honorary Academy Award two months later in March and thanked the audience. He wrote about this experience in his 2002 book, My Stroke of Luck, which he hoped would be an “operating manual” for others on how to handle a stroke victim in their own family.

On December 9, 2016, Douglas became a centenarian. He celebrated his 100th birthday at the Beverly Hills Hotel, joined by several of his friends and family, including Don Rickles, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Steven Spielberg, his wife Anne, his son Michael and his daughter-in-law Catherine Zeta- Jones. Douglas was described by his guests as being still in good shape, able to walk with confidence into the Sunset Room for the celebration.

Douglas blogs from time to time. Originally hosted on Myspace, his posts have been hosted by the Huffington Post since 2012. He is believed to be the oldest celebrity blogger in the world.