Classical Hollywood cinema or the classical Hollywood narrative, are terms used in film history which designate both a visual and sound style for making motion pictures and a mode of production used in the American film industry between 1927 and 1963. This period is often referred to as the “golden age of Hollywood.” An identifiable cinematic form emerged during this period called classical Hollywood style.

Classical style is fundamentally built on the principle of continuity editing or “invisible” style. That is, the camera and the sound recording should never call attention to themselves (as they might in films from earlier periods, other countries or in a modernist or postmodernist work).

The Golden Age

During the golden age of Hollywood, which lasted from the end of the silent era in American cinema in the late 1920s to the early 1960s, films were prolifically issued by the Hollywood studios. The start of the golden age was arguably marked by the release of The Jazz Singer in 1927, and increased box-office profits for films as sound was introduced to feature films. Most Hollywood pictures adhered closely to a genre—Western, slapstick comedy, musical, animated cartoon, biopic (biographical picture)—and the same creative teams often worked on films made by the same studio. For instance, Cedric Gibbons and Herbert Stothart always worked on MGM films, Alfred Newman worked at Twentieth Century Fox for twenty years, Cecil B. DeMille’s films were almost all made at Paramount, director Henry King’s films were mostly made for Twentieth-Century Fox, etc.

After The Jazz Singer was released in 1927, Warner Brothers gained huge success and was able to acquire its own string of movie theatres, after purchasing Stanley Theatres and First National Productions in 1928. MGM had also owned a string of theatres since forming in 1924, known as Loews Theatres, and the Fox film Corporation owned the Fox Theatre string as well. Also, RKO, another company that owned theatres, formed in 1928, the result of a merger with Keith-Orpheum

Theaters and the Radio Corporation of America

RKO formed in response to the monopoly Western Electric’s ERPI had over sound in films, and began to use their own method, known as Photophone. Paramount, who had acquired Balaban and Katz in 1926, answered Warner Bros. and RKO by buying a number of theaters in the late 1920s. Paramount made its final purchase in 1929, acquiring the individual theaters belonging to the Cooperative Box Office, located in Detroit, in the process dominating the Detroit theater market

a number of theaters in the late 1920s. Paramount made its final purchase in 1929, acquiring the individual theaters belonging to the Cooperative Box Office, located in Detroit, in the process dominating the Detroit theater market .

.

Filmmaking is of course a business , and motion picture companies made money

, and motion picture companies made money by operating under the studio system. The major studios kept thousands of people on salary— actors, producers, directors, writers, stunt men, crafts-persons, and technicians, in addition to the hundreds of theaters they owned across America, theaters that showed their films and that were always in need of fresh material.

by operating under the studio system. The major studios kept thousands of people on salary— actors, producers, directors, writers, stunt men, crafts-persons, and technicians, in addition to the hundreds of theaters they owned across America, theaters that showed their films and that were always in need of fresh material.

Throughout the early 1930s, risqué films and salacious advertising became widespread in the short period known as Pre-Code Hollywood. In 1930, MPDDA President Will Hays created the Hays (Production) Code, which followed censorship guidelines and went into effect after government threats of censorship expanded by 1930. However the code was not enforced until 1934, after the new Catholic Church organization, The Legion of Decency, appalled by Mae West’s very sexual (and successful ) appearances in She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel, threatened a boycott of motion pictures if the code did not go into effect. Those films that failed to obtain a seal of approval from the Production Code Administration had to pay a $25,000 fine and could not profit in the theaters, as the MPDDA effectively controlled every theater in the country through the Big Five studios.

from the Production Code Administration had to pay a $25,000 fine and could not profit in the theaters, as the MPDDA effectively controlled every theater in the country through the Big Five studios.

MGM dominated the industry at this time. The studio boasted the top stars in Hollywood, and was credited for creating the Hollywood star system. MGM’s contracted actors and actresses, including those on loan

for creating the Hollywood star system. MGM’s contracted actors and actresses, including those on loan from other studios, included Clark Gable, Joan Fontaine, Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Jean Harlow, William Powell, Myrna Loy, Gary Cooper, Mary Pickford, Carmen Miranda, Henry Fonda, Rita Hayworth, Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Judy Garland, Ava Gardner, James Stewart, Doris Day, Frank Sinatra, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Vivien Leigh, Grace Kelly, Gene Kelly, Gloria Stuart, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, John Wayne, Mickey Rooney, Barbara Stanwyck, John Barrymore, Audrey Hepburn, Lauren Bacall, Humphrey Bogart, Kirk Douglas, Anna May Wong, and Buster Keaton.

from other studios, included Clark Gable, Joan Fontaine, Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Jean Harlow, William Powell, Myrna Loy, Gary Cooper, Mary Pickford, Carmen Miranda, Henry Fonda, Rita Hayworth, Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Judy Garland, Ava Gardner, James Stewart, Doris Day, Frank Sinatra, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Vivien Leigh, Grace Kelly, Gene Kelly, Gloria Stuart, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, John Wayne, Mickey Rooney, Barbara Stanwyck, John Barrymore, Audrey Hepburn, Lauren Bacall, Humphrey Bogart, Kirk Douglas, Anna May Wong, and Buster Keaton.

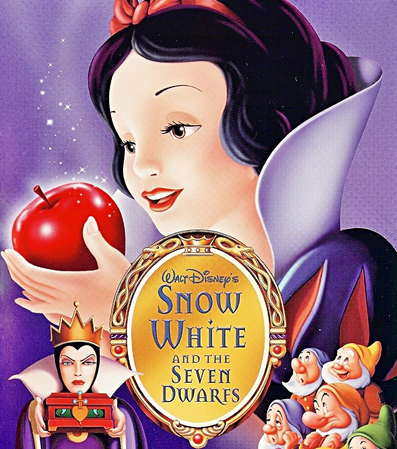

Another great achievement of American cinema during this era came via Walt Disney’s animation efforts. In 1937, Disney

animation efforts. In 1937, Disney created the most successful film of its time, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

created the most successful film of its time, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Film historians have remarked upon the many great works of cinema that emerged from this period of highly regimented filmmaking. One reason this was possible is that, with so many being made, not every film needed to be a big hit. A studio could gamble on a medium-budget feature with a good script and relatively unknown actors. Citizen Kane, directed by Orson Welles and regarded by some as the greatest film of all time, fits that description. In other cases, strong-willed directors like Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and Frank Capra battled the studios in order to achieve their artistic visions. The apogee of the studio system may have been the year 1939, which saw the release of such classics as The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, Stagecoach, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Destry Rides Again

on a medium-budget feature with a good script and relatively unknown actors. Citizen Kane, directed by Orson Welles and regarded by some as the greatest film of all time, fits that description. In other cases, strong-willed directors like Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and Frank Capra battled the studios in order to achieve their artistic visions. The apogee of the studio system may have been the year 1939, which saw the release of such classics as The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, Stagecoach, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Destry Rides Again , Young Mr. Lincoln, Wuthering Heights, Only Angels Have Wings, Ninotchka, Beau Geste, Babes in Arms, Gunga Din, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, and The Roaring Twenties.

, Young Mr. Lincoln, Wuthering Heights, Only Angels Have Wings, Ninotchka, Beau Geste, Babes in Arms, Gunga Din, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, and The Roaring Twenties.

Other films from the golden age now considered to be classics include Casablanca, The Adventures of Robin Hood, It’s a Wonderful Life, It Happened One Night, King Kong, Citizen Kane, Swing Time, Some Like It Hot, A Night at the Opera, Sergeant York, All About Eve, Mildred Pierce, The Maltese Falcon, The Searchers, Breakfast At Tiffany’s, Laura, North by Northwest, Dinner at Eight, Morocco, Rebel Without a Cause, Rear Window, Double Indemnity, Mutiny on the Bounty, City Lights, Red River, Suspicion, High Noon, The Manchurian Candidate, Bringing Up Baby, Meet John Doe, Singin’ in the Rain, Ben-Hur, To Have and Have Not, Roman Holiday, Giant, Jezebel, A Streetcar Named Desire, East of Eden, From Here To Eternity, and On the Waterfront.

Style

The style of classical Hollywood cinema, as elaborated by David Bordwell, was heavily influenced by the ideas of the Renaissance and its focus on humanity.

Classical narration always progresses through psychological motivation, i.e. by the will of a human character and his or her struggle with obstacles toward a defined goal. Space and time are subordinated to the narrative element which is usually composed of two lines of action : a romance intertwined with a more generic thread, such as a business

: a romance intertwined with a more generic thread, such as a business deal or, in the case of Alfred Hitchcock films, solving a crime.

deal or, in the case of Alfred Hitchcock films, solving a crime.

Time in classical Hollywood is continuous, since non-linearity calls attention to the illusory workings of the medium. The only permissible manipulation of time in this format is the flashback. It is mostly used to introduce a character’s memory sequence , such as Bogart’s in Casablanca.

Similarly, the treatment of space in classic Hollywood strives to overcome or conceal the two-dimensionality of film (“invisible style”), and is strongly centered on the human body. The majority of shots in a classical film focus on gestures or facial expressions (medium-long and medium shots). André Bazin once compared classical film to a photographed play in that the events seem to exist objectively, with cameras simply serving to give us the best view of the entirety of the play.

This treatment of space consists of four main aspects: centering, balancing, “frontality,” and depth. Persons or objects of significance are mostly in the center of the frame and are never out of focus. Balancing refers to visual composition, i.e. characters are evenly distributed throughout the frame. Action is subtly addressed

is subtly addressed toward the spectator (frontality), and set, lighting (mostly three-point lighting), and costumes are designed to separate foreground from the background (depth).

toward the spectator (frontality), and set, lighting (mostly three-point lighting), and costumes are designed to separate foreground from the background (depth).

Narrative

The classic Hollywood narrative is structured with an unmistakable beginning, middle, and end. There is usually a distinct resolution at the end. Utilizing actors, events, causal effects, main points, and secondary points are basic characteristics of this type of narrative. The characters in classical Hollywood cinema have clearly definable traits, are active, and very goal oriented. They are causal agents motivated by psychological rather than social concerns.

Production

The mode of film production during this period came to be known as the “Hollywood studio system” as well as “the star system,” an approach that standardized the way movies were produced. All film workers (actors, directors, etc.) were employees of a particular film studio. This resulted in a certain uniformity to film style. Directors were encouraged to think of themselves as employees rather than artists, and hence “auteurs” did not flourish (although some directors, such as Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, and Howard Hawks worked within this system and still managed to fulfill their artistic visions).

The “Big Eight” studios controlled the Hollywood studio system, however among these the Big Five fully integrated studios — MGM, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox, Paramount, and RKO — were the most powerful. They operated their own theater chains, and produced and distributed films as well. The “Little Three” studios (Universal Studios, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists) were also full-fledged film factories, but they lacked the financial resources of the Big Five and therefore produced fewer A-class features that were the foundation of the studio system.

Periodization

Hollywood classicism gradually declined with the collapse of the studio system, the advent of television, the growing popularity of auteurism among directors and the increasing influence of foreign films and independent filmmaking.

The 1948 U.S. Supreme Court decision, which outlawed the practice of block booking and the above-mentioned ownership and operation of theater chains by the major film studios (as it was believed to constitute anti-competitive and monopolistic trade practices) was a major blow to the studio system. The way was cleared for a growing number of independent producers (some of them the actors) and other studios to produce their film product free of major studio interference. The decision effectively killed the original business

of major studio interference. The decision effectively killed the original business model and left studios struggling to adapt.

model and left studios struggling to adapt.

At the time of the Court decision, the assumption was the quality, consistency, and availability of movies would go up and prices would fall. Quite the opposite happened. By 1955, the number of produced films had fallen by 25 percent. More than 4,200 theaters (or 23 percent of the total) had shut their doors. More than half of those remaining were unable to earn a profit. They could not afford to rent and exhibit the best and most costly films, the ones most likely to compete with television. The classical period was at an end.